Scenario Planning – A Process to Manage Uncertainty

Our recent blog posts focused on environments where uncertainty reigns and some interesting business strategies for adapting to these dynamic environments. Now, I’ve teamed up with Steve Player to discuss an important tool that organizations use to peer out into this fog of uncertainty: scenario planning. Steve and I have had a few lively discussions where we’ve deliberated over various aspects of the scenario planning process! This blog post seeks to share the highlights of that conversation.

For those that don’t know Steve, he is an author, international speaker, and management consultant with over three decades of experience helping companies to improve their corporate performance management. He has been at the forefront of activity-based costing, beyond budgeting, business forecasting, and, honestly, all aspects of corporate performance management. I welcome Steve to this conversation.

To begin this post, we start with what scenario planning is and why it’s done. Then, we briefly consider its origins, walk through the process, and warn you about a few pitfalls to avoid along the way.

What Scenario Planning Is and Why We Do It

So, what is scenario planning? Well, in a nutshell, it’s storytelling about the future. Scenarios are plausible narratives about different ways the future could look. Right off the bat, though, we should distinguish scenario planning from forecasting, which attempts to estimate a most likely future. A forecast is mainly a mathematic model of financial outcomes built off an extrapolation of business drivers —where market demand is headed, what sales are expected to be delivered, whether costs will rise or fall next quarter, etc. Scenario planning is not prediction. In fact, it’s all about acknowledging prediction’s limits.

Within many companies, the usual thinking about the future assumes it will resemble what has already happened. For this reason, forecasts assume the status quo, or something awfully close to it. But the whole concept of VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity), as epitomized by our current COVID-19 reality, reminds us that we can’t be sure that the status quo will be maintained. Our best guess—the forecast—is only one possibility among many.

Scenario planning can support strategy (on an organization-wide level) or planning (at lower levels) by allowing organizations to think about radically different futures and how the business might best respond to these futures. Embracing this process makes organizational leaders more agile in their thinking, more sensitive to signals that the wind may be shifting, and more prepared to respond as needed – and, we believe that the responses you develop to prepare for future scenarios may also be of practical use today.

A Brief History of Scenario Planning

Before we move on, we should say a word about the origins of scenario planning. Appropriately enough for a process meant to give you an edge over competitors, it actually comes out of military and geopolitical strategizing. Specifically, scenario planning as we know it today grew from the RAND Corporation’s attempts to grapple with a post-WWII world in which the US faced off with the USSR, both armed to the teeth.i It was clear that nuclear weapons were a game-changer, but it was less clear how they had changed the game—since there had never been a nuclear war. In the absence of clear precedents, widely diverging scenarios were used to aid strategists in thinking outside the box of conventional warfare.

From the RAND Corporation, scenario planning made its way into the business mainstream through Shell Oil, which, in the 1970s, famously considered the possibility that world oil prices might be manipulated—shortly before OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) actually did so.ii Shell hadn’t known the shocks were coming, but they had entertained the idea. Their subsequent preparation for the possibility of these shocks made them “future-ready.”iii

How Scenario Planning Works

Scenario planning has been conducted by many different practitioners and organizations over the decades, so the process has taken different shapes. However, there is always an emphasis on narrative. By that, we mean creating an internally consistent future and then reasoning backwards to create a transparent story of how it came about. This leads you to think harder about the factors that could shift your environment away from your projections, and how you could recognize that shift if and when it occurs. It also lets participants in the process think through how they could best respond to these changes.

Future scenarios do not need to be likely to occur, but they should be plausible. If there’s no way it could come about, you probably shouldn’t waste your time thinking about it. Ideally, scenarios should be striking enough to jar participants’ thinking out of the usual tracks and to help them to remember the scenario long after. (To that end, we like Jay Ogilvy’s suggestion to write down newspaper headlines from that imagined future, to immerse participants.)iv

Usually, a team is tasked with creating the scenarios based on interviews or workshops they conduct with executives or managers. Participants might be asked what trends or issues seem most critical to future operations, or even the “three questions [that they] most wanted to pose to the oracle at Delphi about the company’s and industry’s future environment.”v Leveraging the mnemonic STEEP, these factors can cover Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, and Political considerations (These factors are a furthering of those presented by Francis J. Aguilar in the book, “Scanning the Business Environment”).

Preparing for Scenarios with the Action Planning Process

The following is a seven-step action planning process that we like to use when scenario planning:

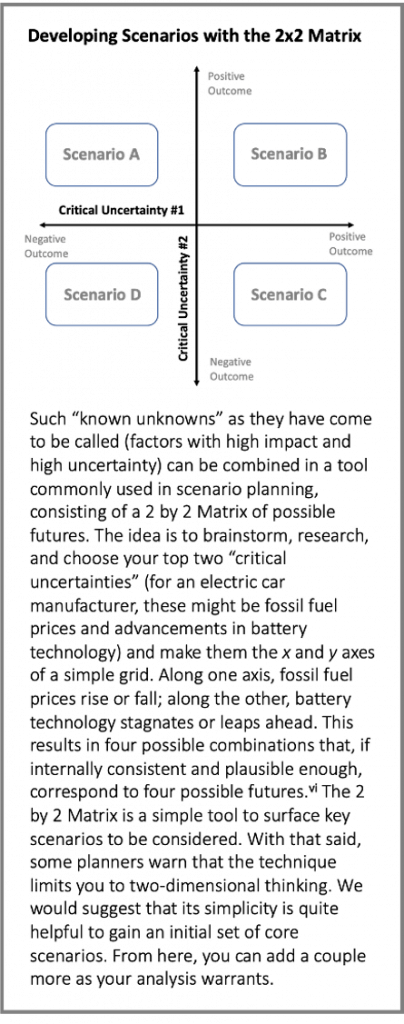

- Develop a diverse set of four to seven potential scenarios. This number of scenarios is enough to force you to think of really different alternatives, but not so many that your team is overwhelmed. (Several techniques exist to identify scenarios. The adjacent call out box outlines one popular method, the 2 x 2 Matrix)

- Articulate the extremes. We strongly advocate including an extremely positive shift in the business environment; a scenario where you can rake in money so quickly you can’t even spend it all. We would also urge you to imagine a negative scenario just as extreme; What would bring the company to the brink of bankruptcy? Starting with two such dramatic scenarios will stretch the team’s thinking and prime them to think about both opportunities and threats.

- Identify what is required to successfully address each scenario. For instance, how could you seize the bounty offered by that first, golden future? And how could you stave off running out of cash in the darkest of times?

- Craft action plans. How should management react in each situation—sell assets to raise cash, launch a new product, merge with a competitor? The specific steps (or plays) in these action plans are similar to how a sports team plans to respond to situations it may encounter in a game – which is why we call this step developing the playbook for specific situations. This approach also helps the organization develop multiple playbooks; each for a different scenario. These plays, developed for a hypothetical future, are often usable in other situations, or even here and now!

- Specify the leading indicators that would alert you that these scenarios are actually occurring. What would the earliest warnings be, the faintest signals? Once you’ve identified them, start tracking them.

- Select the action triggers. It’s not enough to start watching customer requests or developing technologies; you need to decide what threshold will trigger your action plan.

- Refresh and expand your action plans. Periodically revisit existing scenarios to bring them up to date, brainstorm new scenarios to build out your organizational playbook and retire the ones that are no longer needed. In addition, don’t just think about the action plans you can execute now, but the ones you’d like to be able to execute. Then, build out your capabilities to create new plays which can make them real options.

By using the steps above, you stretch your thinking to consider the possibilities of the future and you begin to prepare yourself to respond, if and when those potential futures present themselves.

Traps to Avoid

When conducting the scenario planning process, there are a few pitfalls to watch out for.

One danger is to create too few scenarios. For instance, three is a bad number because there’s a tendency to make two of them extreme and then focus on the safer, middle scenario, Goldilocks style. This negates the point of scenario planning, which is to take seriously a broad range of futures.

A second related danger is to make sure you don’t focus only on downsides. You don’t want to be so ready to make lemonade that you’re unprepared when life hands you oranges!

A third danger is to focus on lagging indicators that will only surface once something has already changed. Instead, you must focus on leading indicators of any big shifts coming in your environment. A good example of a leading indicator is customer inquiries about a new kind of product or service. A lagging indicator might be customer account delinquencies, letting you know there’s a problem once it’s too late.

We also like Gerald Harris’s list of problem areas in scenario planning:vii

- Falling into sensitivity analysis: Sensitivity analysis changes only a couple of variables rather than imagining a really new future; this doesn’t free participants to think outside the box (similar to the first danger)

- Ignoring critical uncertainties: Inattention to the real threat or key factor in your environment can come back to bite you

- The weakness of positive thinking: Assuming the waters will remain calm and that your business will avoid any major disruptions stops you from being really alert (which is the opposite of the second danger)

- Poor research: While just brainstorming uncertainties, trends, and futures is a nice start, good research is needed for a truly useful scenario

To summarize, scenario planning is a tool that more organizations should use as way to deal with our highly volatile, ever-changing world. It prompts teams to stretch their thinking and to become alert to leading indicators of shifts. It can even help you find new game plans for the here and now. We are all prone to assuming tomorrow will look a lot like yesterday, but the pandemic has for sure turned that assumption on its head. Even though you can’t predict the future, you can still make yourself “future-ready”viii for whatever may come your way.

As a postscript, Steve Player is scheduled to deliver a webcast titled “Effective Scenario Planning to Become Future Ready” beginning on April 22nd and repeating again on August 26th and October 18th. This webcast features a list of 10 things to avoid (and what to do instead). His team is also offering a 4-hour training session on Scenario Planning on May 17th, July 12th, September 13th, and November 15th. For Future Ready Finance Events — please connect here to receive more information.

[i] “Learning from the Future” by J. Peter Scoblic, Harvard Business Review, July-August 2020.

[ii] “Living in the Futures: How scenario planning changed corporate strategy” by Angela Wilkinson and Roland Kupers, Harvard Business Review, May 2013.

[iii] “Future Ready: How to Master Business Forecasting” by Steve Morlidge and Steve Player, John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

[iv] “Scenario Planning and Strategic Forecasting” by Jay Ogilvy, Forbes, January 2015.

[v] “Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking” by Paul J. H. Schoemaker, Sloan Management Review, Winter, 1995.

[vi] “Scenario Planning and Strategic Forecasting” by Jay Ogilvy, Forbes, January 2015.

[vii] “Four Blind Alleys of Scenario Analysis” by Gerald Harris, Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 42, No. 6, 2014.

[viii] “Future Ready: How to Master Business Forecasting” by Steve Morlidge and Steve Player, John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

About George Veth

George Veth is a consultant in the areas of strategy execution and initiative management. Most recently, he has been leading a cross-boundary collaboration program with teams from cities across North America and Europe. He lives in Cambridge, MA, and also runs a nonprofit SME Impact Fund in East Africa. His subject matter interests are organizational culture, management [system] innovation, and public value management.

About Steve Player

Steve Player is a consultant focused on improving corporate performance management. He served as Managing Partner of Arthur Andersen’s Advanced Cost Management Team. He co-authored Future Ready: How to Master Business Forecasting (with Steve Morlidge) and Beyond Performance Management (with Jeremy Hope) and five other books on cost management. Steve lives in Addison, TX and runs Future Ready Finance which helps finance teams become forward looking change agents.