Doing Business in Wonderland: The Shifting Sands of Competitive Advantage

As I write this, barely a month into 2021, the US stock market recently swung significantly after an Internet mob bought up shares of GameStop and other seemingly unspectacular companies to undermine the “smart money” (hedge funds that were shorting the stocks). Politics hardly looks more stable, as only three weeks ago an angry mob invaded the US Capitol. All this comes in the middle of a pandemic that has upended lives, and economies, around the globe. At this point, it’s hard to remember what “business as usual” even means.

If you’re struggling to get a handle on the chaos that seems to surround us, you might start with an acronym: VUCA. Standing for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity, the term was popularized by the US military and often used to describe the mercurial situations that have characterized the War on Terror, after the relatively stable stalemate of the Cold War.

Now VUCA has been adopted by the business community, in recognition of a global landscape that sometimes shifts rapidly but in which companies must continue to operate and make strategic decisions. The concept breaks down this way:

- Volatility: Things change more quickly than is typical

- Uncertainty: The future is increasingly hard to predict with confidence

- Complexity: Decision-making is complicated by myriad interrelated factors

- Ambiguity: Even the here-and-now can be difficult to read, as the data resists clear interpretation

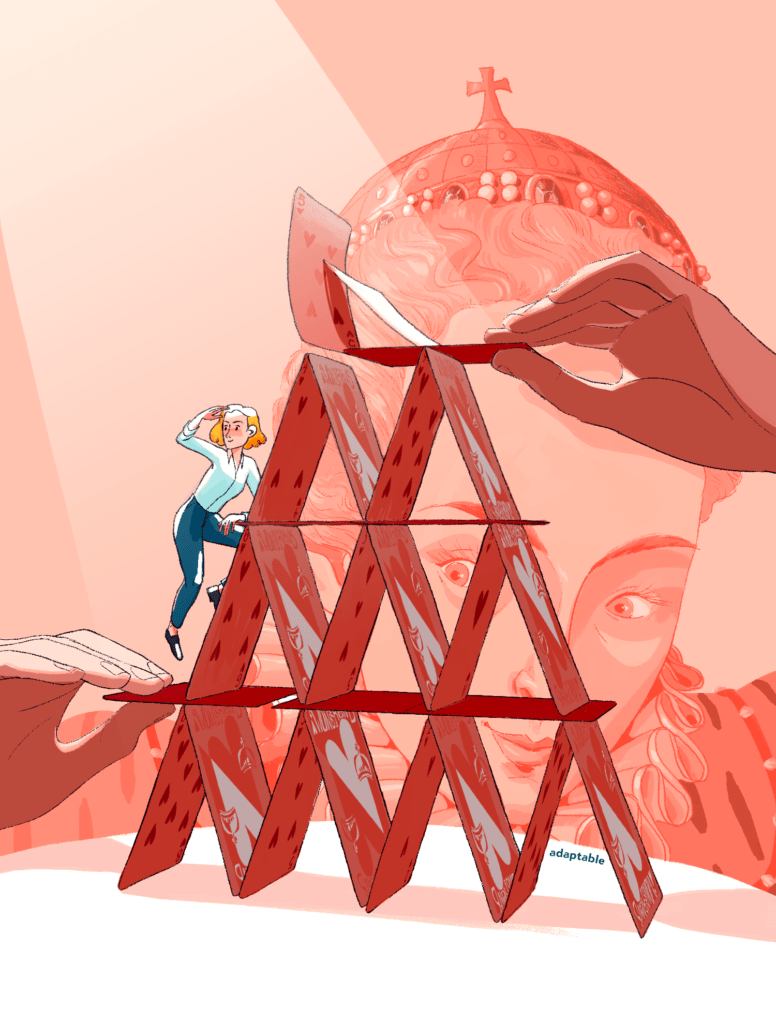

Such conditions were compared to Lewis Carroll’s perplexing Wonderland by authors Rosabeth Moss Kanter, Matthew Bird, Ethan S. Bernstein, and Ryan Raffaelli. They write that Alice falls down the rabbit hole into “a nonsensical world of changing technologies, rules, and fields. There, she struggles to come up with a logic that can give meaning to her environment and guide her expectations and behavior. But each time she works out a law of cause and effect, the rules change.” Similarly, organizational leaders will be caught flatfooted if they try to rely on the rules they are used to, as the terrain shifts under them.

If VUCA describes the quicksand conditions of the contemporary world, what are its causes? Technology is one important factor, as industries and business models are disrupted by new players from Silicon Valley and other tech hubs (like Amazon in retail, or Uber in transportation). Social media has also upset the conventional wisdom about how information is disseminated and how companies relate to their customers. In addition, globalization has impacted every corner of commerce: materials can be sourced from anywhere, assembled anywhere, and sold anywhere—and services are heading that same way. Environmental issues also contribute to instability, especially the overarching threat of climate change, which is forcing people and governments to change the way they do business, even as temperatures and weather patterns are already being affected unpredictably. Politics can contribute to VUCA as well, from Brexit to antidemocratic coups.

While not every month will be as chaotic as January 2021, organizational leaders must nonetheless be prepared for VUCA conditions at any time, since they can arise unexpectedly. This raises a question: How is it possible to ready ourselves for conditions that are, by definition, uncertain? How can a company, institution, or nonprofit weather a storm that could appear at a moment’s notice, and from inside which it is impossible to see a clear way out? Even though decision making is hampered by VUCA, decisions must still be made.

According to an influential 1997 article by David Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen , what organizations need to survive and thrive amid change is dynamic capabilities. These are distinct from the ordinary capabilities that allow an organization to function in normal times, such as being able to source materials reliably, or manufacture products efficiently, or coordinate far-flung employees.

By contrast, dynamic capabilities enable an organization to rapidly respond to an evolving environment. Broadly speaking, they can be divided into three categories: sensing change, seizing opportunities, and transforming the organization.

The first category, sensing, suggests the importance of an organization having its antennae alert to new signals. Is demand fluctuating unexpectedly? Are salespeople hearing about new needs or concerns from customers? Are rivals making sudden moves? Though the signals will often come from an organization’s periphery, they must be relayed speedily to decision makers.

Of course, information is useless without the potential to act on it. Seizing opportunities refers to an organization’s ability to actually change its day-to-day operations, to do things differently, to innovate. Can a new system for interacting with customers be put in place? Can a new line of products be developed to answer a growing need?

Finally, transforming involves changes that go beyond the choice of what products to manufacture or what services to provide. Transforming requires an organization to alter its entire architecture or orientation. Think of the Transformers—those robotic stars of Saturday morning cartoons and blockbuster movies. To adapt to a new situation, such as combat or flight, the Transformer’s body changes into a more appropriate shape. Just so, truly adaptable companies must be able to reconfigure themselves to survive in a VUCA environment. An example is Procter & Gamble’s restructuring of the past decade, as it dropped less profitable brands to focus on the most profitable product lines.

Taken together, these three categories of dynamic capabilities—sensing, seizing, transforming—are the capacities that make an organization agile, adaptable, and responsive to an environment that may shift at any moment. Though a question remains as to how best to cultivate these capabilities and at what level of the organization to focus, wise leaders will pay careful attention to their development.

In my next two blog posts, I’ll continue exploring some of the themes raised here. First, I’ll talk about a few recent articles from consulting firms about different approaches to navigating unstable business environments. These articles suggest that firms consider creating entirely new engines for growth, establishing corporate venture funds, or taking an ecosystems approach. After that, I’ll address one potential cause of market instability: changing views of the purpose of the corporation itself.

__________________________________

[i] “How leaders use values-based guidance systems to create dynamic capabilities” by Rosabeth Moss Kanter, Matthew Bird, Ethan J. Bernstein, and Ryan Raffaelli

[ii] “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management” by David Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen

[iii] “Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership” by Paul J. H. Schoemaker, Sohvi Heaton, and David Teece